INTERVIEWING FOR SCENE

NOTE: What follows is in an excerpt from a series on narrative interviewing published on Nieman Storyboard, Harvard University’s platform dedicated to the craft of narrative storytelling. Several undergraduate and graduate narrative writing classes assingn all or parts of the series as readings. Find the whole series here:

Phase IV: Interviewing for scene

The last major phase of interviewing for narrative usually occurs just before (or precisely when) I’m ready to sit down and write. My story is solid. I know my central character and the arc of the story’s journey. I’ve identified pivotal moments and structure in mind. Now I need to fill in those scenes with detail and movement. I’ve chosen the pivotal moments worthy of cinematic scenes.

At this phase of the process, the questions get very granular. I start interrupting and saying, “Wait. Let’s back up. Do you mean…?" As the character is speaking, I’m constantly pressing for more specificity. More detail. The more concrete the detail, the more crisp the image in the reader’s mind.

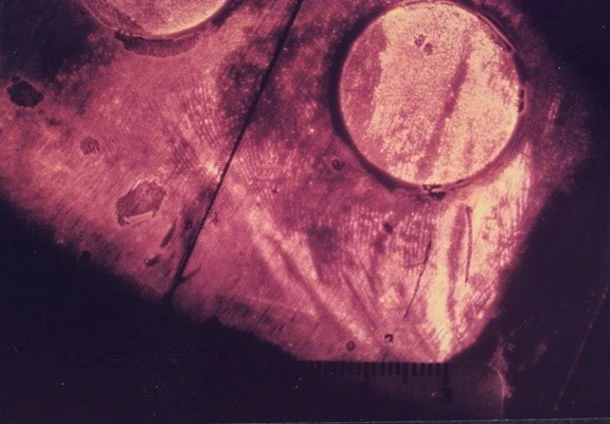

Here’s a bit of an interview transcript for a chapter in my book, In Light of All Darkness, about a historic kidnapping. I’m trying to elicit a play-by-play from an FBI agent, the Evidence Response Team member who lifted a partial palm print from Polly Klaas’s bunkbed frame using the then-brand-new technology of fluorescent powder and Alternate Light Source (forensic light).

Q: So you’re dusting Polly’s bed frame with fluorescent powder. In one interview, you said “orange.” In another you said “red.”

A: They call it REDWOP, but it’s a fluorescent orange.

Q: Because REDWOP is “powder” spelled backwards, right?

A: Yes.

Q: So you scanned the whole room with the (forensic) light before you put on any powder?

A: I would have done an overall scan of the room. Then I would have gone to the target I was looking at, which was the bed.

Q: Why was that the target?

A: That was an object that was doable. And it was within arm’s reach of the suspect. Proximity. So I went close to the floor and I did test patterns with different powders.

Q: Are you talking about the bottom of the bed frame?

A: Down by the floor, at the bottom, where I knew the suspect could not have touched.

Q: By “bottom” do you mean the horizontal piece of wood along the mattress? Or the vertical leg of the bed frame?

A: It was on the vertical leg.

Q: And were you wearing goggles?

A: I was.

Q: So you first would have turned off the lights, right?

A: Yes.

Q: Would you have closed the door?

A: Correct. I needed as much total darkness as I could get. The darker the room, the better the light fluoresces.

I later realized that it looks a lot like the trial transcripts I was reading, in which a trial lawyer is examining a witness on the stand. In a way, the lawyer and the reporter have a similar objective: elicit a narrative with such crisp detail that a jury member, or reader, can imagine it vividly.

As the character is speaking, I’m trying to see what they are seeing on the silver screen of memory. My friend and fellow narrative journalist Bronwen Dickey likes to say, “Pretend I’m a GoPro.” I like to see not only what the character is seeing in that moment, but also understand what they’re thinking about it. I hunt for internal dialogue.

Q: What was it about REDWOP that worked better? Could you describe what the green looked like, and what you were not seeing that you wanted to see?

A: With the green, there was not enough reflective material on the bed. It did not define for my eyes any fingerprints at all.

Q: So then what did the REDWOP look like?

A: I could see a palm print. I could see fingerprints. I could see residue from the black powder used by the police department. I could see smudges. My difficulty was that the palm print I saw was over a round disc, which was plastic. Normally, powder will adhere to plastic but not to wood.

Q: Is there a word that pops into your head when you’re like, “That’s it!”

A: I would normally just say, “Oh my!”

I’m constantly pressing for more specificity — for telling details and concrete imagery low on the Ladder of Abstraction. Evidence, you say? What kind of evidence? Fingerprints? Which hand? Which finger? Was it a loop, an arch, or a whorl?

Some people are more visually inclined than others. Some have better vocabularies or ways of describing a scene. I ask my story characters if they have photos, videos, text messages or other visual aids. If we flip through a photo album, I’ll point to certain objects, hoping to unearth a telling detail. (A “telling detail” is something that reveals character, yields insight or advances the narrative; it’s more than a bit of scenery.) If I need to take the reader inside a house that no longer exists, I’ll ask them to draw me a floor plan.

As the scene starts to come together in my mind, I’ll plumb it for meaning and try to see it through a particular Point of View. (The best definition of POV came from my son when he was in fifth grade: “It means, ‘Whose head are you in?’”). I try to write a scene through the Point of View of only one character in that scene to avoid what I think of as “head hopping.”) To do that, I need to get inside that character’s head. Some of my favorite questions for doing so are:

What did that look like?

How so?

What do you mean?

How did that feel?

Why do you think that is?